Acute management of fracture

Acute management of fracture

Fracture management can be divided into non operative and operative techniques. The non operative approach consists of a closed reduction if required, followed by a period of immobilization with casting or splinting. Closed reduction is needed if the fracture is significantly displaced or angulated. Paediatric fractures are generally much more tolerant of non operative management, owing to their significant re modelling potential.

If closed reduction is inadequate, surgical intervention may be required. Indications for surgical intervention include the following:

The most important factors in fracture healing are blood supply and soft-tissue health, and initial management of an injured limb should have the goal of maintaining or improving these.

The initial management of fractures consists of realignment of the broken limb segment (if grossly deformed) and then immobilizing the fractured extremity in a splint. The distal neurologic and vascular status must be clinically assessed and documented before and after realignment and splinting. If a patient sustains an open fracture, achieving haemostasis as rapidly as possible at the injury site is essential; this can be achieved by placing a sterile pressure dressing over the injury site.

Splinting is critical in providing symptomatic relief for the patient, as well as in preventing potential neurologic and vascular injury and further injury to the local soft tissues. Patients should receive adequate analgesics in the form of acetaminophen or opiates, if necessary.

Open fractures

The treatment goals for open fractures are as follows:

-

-

To prevent infection

-

-

-

To allow the fracture to heal

-

-

To restore function in the injured limb

Once the initial assessment, evaluation, and management of any life-threatening injury are completed, the open fracture is treated. Haemostasis should be obtained if there is significant ongoing bleeding, though bone bleeding is best reduced by anatomic reduction. Gross contaminants can be removed if possible and the soft-tissue wound can be covered by a sterile dressing moistened with normal saline. Harsher adjuncts, such as iodine solutions, are not recommended, because of their cytotoxic effects. [41] Tetanus immunization should be provided if the patient does not have current immunity.

Non operative Therapy

Early fracture management is generally aimed at controlling haemorrhage, providing pain relief, preventing ischemia-reperfusion injury, and removing potential sources of contamination (foreign body and nonviable tissues). Once these tasks are accomplished, the fracture should be reduced and the reduction should be maintained, which will optimize the conditions for fracture union and minimize potential complications.

The ultimate goal of fracture management is to ensure that the involved limb segment, when healed, has returned to its maximal possible function. This is accomplished by obtaining and subsequently maintaining a reduction of the fracture with an immobilization technique that allows the fracture to heal and, at the same time, provides the patient with functional aftercare. Either nonoperative or surgical means may be employed.

Nonoperative (closed) therapy consists of casting and traction (skin and skeletal traction).

Casting

Closed reduction should be performed initially for any fracture that is displaced, shortened, or angulated. This is achieved by applying traction to the long axis of the injured limb, reversing the mechanism of injury/fracture, and finally immobilizing the limb through casting or splinting. Splints and casts can be made from fiberglass or plaster of Paris. Barriers to accomplishing reduction include soft-tissue interposition at the fracture site and hematoma formation that create tension in the soft tissues.

Closed reduction is contraindicated in the following circumstances [13] :

-

-

If there is no displacement

-

-

-

If displacement exists but is not relevant to functional outcome (eg, humeral shaft fracture where the shoulder and elbow motion can compensate for residual angulation)

-

-

-

If reduction is impossible (severely comminuted fracture)

-

-

-

If the reduction, when achieved, cannot be maintained

-

-

If the fracture has been produced by traction forces (eg, displaced patellar fracture)

Traction

For hundreds of years, traction has been used for the management of fractures and dislocations that cannot be treated by means of casting. With the advancement of orthopedic implant technology and operative techniques, traction is rarely used for definitive fracture/dislocation management. Two types of traction exist: skin traction and skeletal traction.

Skin traction

In skin traction, traction tapes are attached to the skin of the limb segment that is below the fracture or a foam boot is securely fitted to the patient’s foot. In the application of skin traction, or Buck traction, usually 10% of the patient’s body weight (up to a maximum of 10 lb) is recommended. [38] At weights greater than 10 lb, superficial skin layers are disrupted and irritated. Because most of the forces created by skin traction are lost and dissipated in the soft-tissue structures, skin traction is rarely used as definitive therapy in adults; rather, it is commonly used as a temporary measure until definitive therapy is achieved.

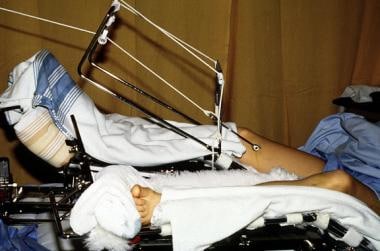

Skeletal traction

In skeletal traction, a pin (eg, a Steinmann pin) is placed through a bone distal to the fracture. Weights are applied to this pin, and the patient is placed in an apparatus to facilitate traction and nursing care. Skeletal traction is most commonly used in femur fractures: A pin is placed in the distal femur (see the image below) or proximal tibia 1-2 cm posterior to the tibial tuberosity. Once the pin is placed, a Thomas splint is used to achieve balanced suspension.

Surgical Therapy

The four AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen [Association for Osteosynthesis]) principles, in their basic form, have governed the society’s approach to fracture management for decades. [6] They are as follows:

-

-

Anatomic reduction of the fracture fragments – For the diaphysis, anatomic alignment ensuring that length, angulation, and rotation are corrected as required; intra-articular fractures demand anatomic reduction of all fragments

-

-

-

Stable fixation, absolute or relative, to fulfill biomechanical demands

-

-

-

Preservation of blood supply to the injured area of the extremity and respect for the soft tissues

-

-

Early range of motion (ROM) and rehabilitation

Ilizarov fixator.

Polytrauma: early total care vs damage-control orthopedics

Soft-tissue injuries and potential open wounds are inflammatory foci that behave much like an endocrine organ by releasing mediators and cytokines both locally and systemically, leading to a systemic inflammatory response. Further surgical insult (ie, femoral nailing for a femur fracture) can aggravate this mediator response, resulting in a further immunologic response, known as the “second hit” phenomenon. [50] This, in turn, may exacerbate the patient’s clinical status and can lead to further morbidity as well as mortality.